From a theological perspective, it is important to emphasise that a procession is a sign of the Church’s condition, the pilgrimage of the People of God, with Christ and after Christ, aware that in this world it has no lasting dwelling. Through the streets of this earth it moves towards the heavenly Jerusalem. It is also a sign of the witness to the faith that every Christian community is obliged to give to the Lord in the structures of civil society. It is also a sign of the Church’s missionary task which reaches back to her origins and the Lord’s command (cf. Mt 28, 19-20), which sent her to proclaim the Gospel message of salvation.

Processions have been events in public life — religious or secular — for as far back as there are written records. In every culture, public anniversaries, triumphant heroes, religious festivals, and innumerable other events have been marked by parades of local leadership and activists — and participated in by the viewers. In this way, the entire community is able to reaffirm its values and traditions, while inspiring onlookers with a sense of purpose.

Processions have been events in public life — religious or secular — for as far back as there are written records. In every culture, public anniversaries, triumphant heroes, religious festivals, and innumerable other events have been marked by parades of local leadership and activists — and participated in by the viewers. In this way, the entire community is able to reaffirm its values and traditions, while inspiring onlookers with a sense of purpose.

There are numerous accounts of such in the Bible, from organized affairs such as processions with the Ark of the Covenant, to the impromptu one surrounding the entrance of Our Lord into Jerusalem on the first Palm Sunday. With this background, and that of the Roman Imperial tradition (the Triumphs of victorious generals being the best known example), it is not surprising that the Church began to incorporate such practices into her own life shortly after she was legalised by Constantine.

BREGNO, Andrea, The Apparition of St Michael to St Gregory, c. 1469, Marble, San Gregorio Magno, Rome

Although the first Christian processions took place firmly within the Liturgy (Introit, Offertory, and Gospel), they soon moved out of doors. The type of prayer called “litany” today was expressly designed for these functions, wherein the Church would offer prayers for all degrees of folk within both Church and State, invoking the intercession of the Blessed Virgin and various Saints. In 375, St. Basil mentioned one such in a letter, followed by St. Ambrose in 388 — both letters spoke of this practice as long established. In periods of plague or famine, processions bearing saints’ relics would be held, begging Heaven for an end to the calamity. The participants might be barefooted and even literally covered with sackcloth and ashes — such catastrophes were seen as Divine punishments requiring penance. It was in the course of one of these processions in 590 that Pope St. Gregory the Great had a vision of the Archangel St. Michael atop Hadrian’s Mausoleum sheathing his sword. The plague ceased from that moment, and the building has been called Castel Sant’ Angelo ever since.

But early on, it was recognized that such processions could also be held to ask for future blessings as well. Pope Liberius (352-366) ordered the litaniae majores et minores, processions of clerics and laymen in the city of Rome that would set of along a prescribed path, chanting the Litany of the Saints. The “Greater Litanies” were to be held on the feast of St. Mark, and the Lesser on the three days before Ascension Thursday. Their goal was to be twofold: to atone for past sins on the part of the people, and to seek blessing for the crops and a fruitful harvest. They were introduced into Gaul in 470 by St. Mamertus, Bishop of Vienne, and ordered for the entirety of the Western Church by Pope St. Leo III in 800. The period of the Lesser Litanies came to be called the “Rogation Days,” on each of which a procession would set off along the boundaries of each parish. As time went on, these became more and more a rural observance, and in 1969 the Rogation Days were removed from the Missal by Paul VI. But in recent years there has been a revival of the observance in rural parishes, not only among Catholics but Lutherans and Episcopalians as well. Since the promulgation of Benedict XVI’s motu proprio in 2007 reviving the general use of the Traditional Latin Mass, those communities using it have increasingly observed the Rogations.

The Roman Rituale (the latest edition of which is called in English simply “The Rites”) carries extensive instructions regarding processions. They are distinguished as “Ordinary Processions:” for feast days, such as Candlemas, Palm Sunday, Holy Week, the Rogation Days, Corpus Christi, and other feasts (such as patron saints) as dictated by local custom; and “Extraordinary Processions:” order for particular reasons — asking for good weather or rain; for an end to war, famine, plague, storm or other catastrophes; to offer thanksgiving for some blessing received; to translate relics; or to dedicate a church or cemetery. There are also processions to honor a new bishop or a royal.

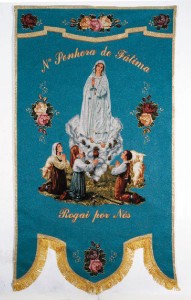

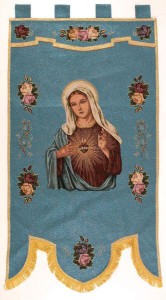

There are also set instructions governing procedure. In good weather, the participants are to be bare headed, and clerics and layfolk, men and women to walk separately. The cross should be at the head of the procession, and there can be banners.

But these stark instructions do not reflect the richness and variety of processions through the history of the Church. Some have been and (in some places) are, very elaborate indeed. In addition to the officiating clergy and acolytes, there are very often knightly orders and various devotional confraternities and sodalities, often in splendid costumes. In Catholic regions, local civic authorities, such as the mayor and city council frequently take part. The Corpus Christi Procession, in particular, has seen soldiers and sovereigns take part, as elements of society offer homage to the Blessed Sacrament. There are in some places even processions on horseback or of boats. In past times, there might even be representations of various Church doctrines or biblical and historical episodes — the famous Mystery and Miracle Plays.

But these stark instructions do not reflect the richness and variety of processions through the history of the Church. Some have been and (in some places) are, very elaborate indeed. In addition to the officiating clergy and acolytes, there are very often knightly orders and various devotional confraternities and sodalities, often in splendid costumes. In Catholic regions, local civic authorities, such as the mayor and city council frequently take part. The Corpus Christi Procession, in particular, has seen soldiers and sovereigns take part, as elements of society offer homage to the Blessed Sacrament. There are in some places even processions on horseback or of boats. In past times, there might even be representations of various Church doctrines or biblical and historical episodes — the famous Mystery and Miracle Plays.

Prior to the Reformation, this “culture of processions” was universal in the Church, East and west. But the first Protestants often rejected most processions as “Popish” idolatry and superstition. So while in traditionally Catholic parts of Europe, Latin America, and certain parts of Asia and Africa, the old customs hold forth (and are often major tourist draws to localities that still have them), they died out in such Protestant regions as Scotland and England, and were forbidden in Ireland by the British authorities. In time, Catholics in those lands — and the countries overseas where they settled, forgot the old ways. Where processions were required by the Missal, as at Candlemas, Palm Sunday, and Corpus Christi, they were held in the churchyard or even restricted to marching around the interior of the Church; they might even be done away with altogether.

Prior to the Reformation, this “culture of processions” was universal in the Church, East and west. But the first Protestants often rejected most processions as “Popish” idolatry and superstition. So while in traditionally Catholic parts of Europe, Latin America, and certain parts of Asia and Africa, the old customs hold forth (and are often major tourist draws to localities that still have them), they died out in such Protestant regions as Scotland and England, and were forbidden in Ireland by the British authorities. In time, Catholics in those lands — and the countries overseas where they settled, forgot the old ways. Where processions were required by the Missal, as at Candlemas, Palm Sunday, and Corpus Christi, they were held in the churchyard or even restricted to marching around the interior of the Church; they might even be done away with altogether.

Catholic Emancipation in Protestant Europe, and the presence of ethnic Catholics in North America, led to a gradual revival of processions in some areas — but they were often considered unusual, and looked at with some suspicion by “native” Catholics, despite, for example, Pius XI call for processions honoring the new feast of Christ the King. The liturgical movement did a great deal of work expanding the use of processions prior to Vatican II. But after that Council, due to the kinds of misinterpretations of its spirit of the sort repeatedly denounced by John Paul II and Benedict XVI, many places, even in Catholic countries, did away with some or all of them, or at least cut them back in number or length.

To correct these abuses (and many others which had afflicted popular piety since the Council), in 2001 the Congregation for Divine Worship issued a Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy. Throughout that document, the use (and revival) of processions for various Church festivals is called for, and an entire section devoted to processions alone, in which their importance for all Catholics is underlined. The need for popular piety (and so for processions) was explained by the Congregation in the Directory’s Introduction:

Following on the conciliar renewal, the situation with regard to Christian popular piety varies according to country and local traditions. Contradictory attitudes to popular piety can be noted: manifest and hasty abandonment of inherited forms of popular piety resulting in a void not easily filled; attachments to imperfect or erroneous types of devotion which are estranged from genuine Biblical revelation and compete with the economy of the sacraments; unjustified criticism of the piety of the common people in the name of a presumed “purity” of faith; a need to preserve the riches of popular piety, which is an expression of the profound and mature religious feeling of the people at a given moment in space and time; a need to purify popular piety of equivocation and of the dangers deriving from syncretism; the renewed vitality of popular religiosity in resisting, or in reaction to, a pragmatic technological culture and economic utilitarianism; decline of interest in popular piety ensuing on the rise of secularized ideologies and the aggressive activities of “sects” hostile to it.

Following on the conciliar renewal, the situation with regard to Christian popular piety varies according to country and local traditions. Contradictory attitudes to popular piety can be noted: manifest and hasty abandonment of inherited forms of popular piety resulting in a void not easily filled; attachments to imperfect or erroneous types of devotion which are estranged from genuine Biblical revelation and compete with the economy of the sacraments; unjustified criticism of the piety of the common people in the name of a presumed “purity” of faith; a need to preserve the riches of popular piety, which is an expression of the profound and mature religious feeling of the people at a given moment in space and time; a need to purify popular piety of equivocation and of the dangers deriving from syncretism; the renewed vitality of popular religiosity in resisting, or in reaction to, a pragmatic technological culture and economic utilitarianism; decline of interest in popular piety ensuing on the rise of secularized ideologies and the aggressive activities of “sects” hostile to it.

John Paul II was particularly interested in this issue. In his last Encyclical, Ecclesia de Eucharistia, announcing the Year of The Eucharist (the end of which, sadly enough, he did not live to see), he wrote, “The devout participation of the faithful in the Eucharistic procession on the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ is a grace from the Lord which yearly brings joy to those who take part in it.” As a result, that year saw the revival of the Corpus Christi procession in many places from which it had long been absent. Benedict XVI has echoed his predecessor’s call for a renewal of processions and other form of public expression of the Faith.

In California, and Los Angeles in particular, the Church is in a unique position. In one sense, State and City are historically among the northernmost outposts of Latin America; they are also the Westernmost extension of the United States, and at the same time the focus of an incredible number of cultures from around the globe. The presence of these three realities has given rise in the Church, to a rich tradition of processions.

In California, and Los Angeles in particular, the Church is in a unique position. In one sense, State and City are historically among the northernmost outposts of Latin America; they are also the Westernmost extension of the United States, and at the same time the focus of an incredible number of cultures from around the globe. The presence of these three realities has given rise in the Church, to a rich tradition of processions.

Bl. Junipero Serra, the Apostle of California, had a great love of processions and all the ceremonies of the Church. When founding Monterey and Mission Carmel with Gaspar de Portola, on June 1, 1770, it was agreed that the actual dedication would be two days later, on Pentecost Sunday. On that day, Fr. Serra said Mass under a tree where the Carmelites who had accompanied the Spanish explorer Vizcaino to that site in 1602 had said Mass. Portola, having declared that the King of Spain’s intention was first of all to spread the Faith, ordered that the cross should precede the Spanish flag, and Fr. Serra should lead the procession to the site where the new mission was to be planted. There the padre offered a prayer; with that Mass and procession, the life of both Carmel Mission and the first capital of California were begun.

On July 2, Fr. Serra wrote a letter to Jose de Galvez, Viceroy of New Spain, wherein he detailed the fledgling settlement’s first celebration of Corpus Christi. “I wrote at great length of all these things by letter of the sixth of last month, taken south by the couriers who set out from this place on the solemn day of Corpus Christi. And although they may well have passed on the word that we were going to celebrate the Feast and Procession of the Most Blessed Sacrament on that day, and since the letters of the gentlemen who finished their reports later than I may not even have mentioned the fact, I now repeat that it was actually carried out, and indeed with such splendor that it might well have caused admiration even in Mexico City.”

But as he wrote further on in the letter, it almost did not come off. For although he had a monstrance, he had no processional torches. He thought about canceling the procession. Nevertheless, “I firmly resolved that the ceremony could not be dispensed with, having in mind the case of our Friars in the remote Kingdom of Titlas, who having just arrived among those heathen, and on the occasion of having held a Procession of the Most Blessed Sacrament there, a monstrance was brought to them from Spain by the hands of angels, and through the intercession of the Venerable Mother of Agreda.” He went on to say, that although there was no such miraculous intervention, they did find two large boxes of shiny silver lanterns aboard the ship that no one had known about. The procession went off as splendidly as might be imagined.

But as he wrote further on in the letter, it almost did not come off. For although he had a monstrance, he had no processional torches. He thought about canceling the procession. Nevertheless, “I firmly resolved that the ceremony could not be dispensed with, having in mind the case of our Friars in the remote Kingdom of Titlas, who having just arrived among those heathen, and on the occasion of having held a Procession of the Most Blessed Sacrament there, a monstrance was brought to them from Spain by the hands of angels, and through the intercession of the Venerable Mother of Agreda.” He went on to say, that although there was no such miraculous intervention, they did find two large boxes of shiny silver lanterns aboard the ship that no one had known about. The procession went off as splendidly as might be imagined.

For the rest of his life, Fr. Serra insured that all the processions in the Church’s calendar were celebrated as elaborately as possible. During the Lenten outdoor Stations of the Cross processions, for example, his assistant, Fr. Palou, wrote the cross he carried on his shoulder “was so heavy that I, stronger and younger though I was, could not lift it”.

His attitude toward processions went on amongst his brethren after his death. The splendor of the Franciscan processions was a major factor in attracting Indian converts. Even so late as the 1890s, when the old mission town of San Juan Capistrano was suffering from a severe drought during the absence of a priest, the local catechist, Poblania Montanez, took the matter in hand. She organized her young students into a procession carrying a crucifix and an old statue of St. Vincent that had been rescued from the ruined mission. They marched all the way down to the beach, at which point heavy rains began, to the joy of all concerned.

The same spirit survived in Los Angeles. The L.A. Weekly Star of June 5, 1858 carried a rapturous story on the Corpus Christi proceedings of that year in the Old Plaza. The Bishop celebrated vespers in the Plaza Church, after which a solemn Eucharistic procession made a circuit of the Plaza, stopping at each of the altars that had been set up in front of various houses by their owners. The makeup of the procession was very much in keeping with tradition: the girls of the Sister’s school were in front, bearing their banner — their were 120 of these in two files, dressed in white dresses and veils, and scattering flowers from baskets they held; these were followed by La Placita’s choir boys; behind them came twelve men bearing candles, in honor of the Apostles; these were followed by Fr. Raho and Bishop Amat, carrying the monstrance; four prominent Angelenos carried a “gorgeous canopy.” Behind followed an enormous number of men, women, and children, marching two by two; the whole company was escorted by two militia units, the California Lancers (an Hispanic Unit) and the Southern Rifles. Having made the circuit, the procession returned to the church.

“At the conclusion of mass the pupils of the female school headed by their instructresses, the Sisters of Charity, come out of the church in procession bearing the image Our Lady under a canopy. They were joined by the Lancers and passing around the public church re-entered the church. The appearance of the procession as it left the church and during its march was imposing. The canopy covering the representation of the angelic queen, tastefully ornamented, was borne by girls dressed in white. The girls of the school with their heads uncovered and in uniform white dresses, followed; then came the Lancers, the rear of the company being brought up by a mounted division armed with lances. There was an evening procession on the Plaza.

Although both of these solemnities have long since ceased to be observed, there are a few procession which continue to wend their ay around the Old Plaza. From December 16 to 24, the old custom of Las Posadas is carried out on neighboring Olvera street, in which a candlelight procession, representing the Holy Family, stops at each of the stores and is denied admittance, in memory of the reception Mary and Joseph received in Bethlehem. At their last stop they are received, enter the store singing, and are treated to pan dulce and hot chocolate. Two weeks later, on the Feast of the Epiphany, the procession of the Three Kings winds through the Plaza.

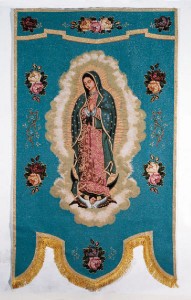

But just as old Pueblo is no longer the entirety of the City of Angels, so too the City’s processional life is now far more widespread. Perhaps the most elaborate observance is the procession in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe in East Los Angeles. For eight decades the mile-long affair has set out from Soledad Church, and brings together people from all over the Archdiocese.

St. Elizabeth’s in Van Nuys sees Peruvians process in honor of their patron, Christ of the Miracles in October, and Costa Ricans do the same for Our Lady of Los Angeles (the national shrine in that country in August. The same month, Salvadorans take to the streets for the Divine Savior at Our Lady of Loretto in Pico-Union.

Processions are not restricted to the city’s Hispanic population, however. At St. Peter’s Italian Catholic Church, on the edge of Chinatown, the year is punctuated by a number of processions as the eleven devotional societies celebrate their patron saint. Four similar societies do the same at St. Mary, Star of the Sea in San Pedro. A recent phenomenon is the ever-growing San Gennaro festival in Hollywood, which prominently features a procession in honor of Naples’ patron saint.

Holy Family Church in Artesia is witness to several processions put on by Portuguese parishioners, in honor of saints dear to them; St. Stephen’s near USC hosts an annual procession honor of the patron of Hungary, complete with a replica of his Holy Crown. There are quite a number of similar ethnic observances scattered around the Archdiocese.

Holy Family Church in Artesia is witness to several processions put on by Portuguese parishioners, in honor of saints dear to them; St. Stephen’s near USC hosts an annual procession honor of the patron of Hungary, complete with a replica of his Holy Crown. There are quite a number of similar ethnic observances scattered around the Archdiocese.

Not all of these processions are inspired by nationality. Reseda in the San Fernando Valley is the scene of a large Corpus Christi procession wending its way five miles down Sherman Way, from St. Bridgid of Sweden via St. Catherine of Siena to St. Joseph the Worker. The cloistered Dominican nuns of the Monastery of Our Lady of the Angels host a procession in honor of Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

In the light of this background, a revived procession in honor of Our Lady, Queen of the Angels, seeking her protection and guidance for us all, will accomplish a number of goals:

- It will serve to unite local Catholics of today with the practice of the Church in every age and country;

- It will be an act of obedience and fidelity to the wishes of the Popes, especially the most recent ones;

- It will be an affirmation of the glorious local Catholic heritage of the Southland;

- It will bring together in unity and diversity all the varied backgrounds and nationalities of the Archdiocese;

- And, it will mark our willingness to dedicate ourselves to the New Evangelization of our native place.

Procession Links

- Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy

http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccdds/documents/rc_con_ccdds_doc_20020513_vers-direttorio_en.html - Grand Marian Procession of Tournai, Belgium

http://users.belgacom.net/Grande_Procession_Tournai/ - Corpus Christi Procession of Toledo, Spain

http://www.corpuschristitoledo.es/ - Holy Week in Seville, Spain

http://www.semana-santa.org/ - Procession of the Holy Blood in Bruges, Belgium

http://www.holyblood.com/NL/00.asp - Revived Mystery Plays in Chester, England

http://www.chestermysteryplays.com/