In an unassuming looking modern building on Ocean View Avenue near downtown Los Angeles sits a medical facility that serves the local poor without charging them; this is the Knights of Malta Free Clinic. If one attends an important ceremony at Our Lady of the Angels Cathedral — such as the annual Red Mass, invoking the Holy Spirit upon the legal and judicial professions — he will see a groups of these knights processing, wearing black mantles with white crosses on them. These two sights are simply the most recent and most local chapters of a story that has gone on over 900 years, and shows no sign of stopping: the tale of the Sovereign Military Order of St. John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes, and of Malta — more commonly called “the Knights of Malta.”

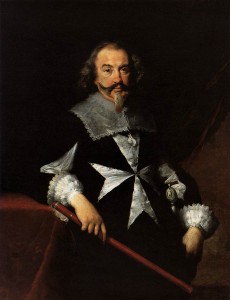

STROZZI, Bernardo, Portrait of a Maltese Knight, Oil on canvas, 129 x 98 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

The knights one may meet working at the clinic or on ceremonial occasions are part of a world-wide organization, based in Rome. It is recognized as an independent country under international law, exchanging ambassadors with over a hundred governments; issuing coins, stamps, and passports; sending an observer to the United Nations; supporting an army; and in every way carrying on like any other sovereign regime. But it is unique. It is not a country, but a religious order — which at the same time is military. The territory over which its word is law is smaller even then the Vatican, consisting of only a palace and a villa in Rome and a small fort in Malta. The major purpose of this government is not exacting taxes out of its citizens or ensuring their political correctness, but almost wholly to aiding the sick and impoverished world-wide through a network of hospitals and clinics, an enormous ambulance corps, emergency relief flights, and guided pilgrimages to Lourdes. Although its membership include some of the most noble of Europeans and wealthiest of Americans, they choose to work with the poorest of the poor — with, as their rule puts it, “our lords, the sick.”

This mission is certainly in keeping with their origins. Even before the First Crusade, there were, near the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, two monasteries — one dedicated to St. John the Baptist, and the other called Santa Maria Latina. During the persecution of native and pilgrim Christians which led to the Crusades, the first monastery was shut down. But it was reoccupied by a group of monks who took to caring for sick pilgrims. Their leader was one now a Blessed — called Gerard de Tonques, whose holiness was matched by his administrative ability.

There are various accounts of how long the institution that Bl. Gerard came from had been there, and for that matter where he himself was from. What is certain is that when Godefroi de Bouillon and his crusaders liberated Jerusalem, they found the Hospital operating at what is now the site of the German Lutheran Church of the Redeemer and the Greek Orthodox Church of St. John the Baptist. Many of the ill and wounded crusaders were treated there, and as a result, Bl. Gerard’s brothers and their new Order of St. John of Jerusalem were given gifts of land in Palestine by Godefroi and his brother, King Baldwin I of Jerusalem. They were able to found branch hospitals in various Mediterranean ports to treat ill pilgrims before they set out for the Holy Land. By the time Bl. Gerard died in 1120, successive Popes had confirmed his order in its privileges and independence.

His successor as head of the order, Bl. Raymond du Puy, militarized the order, to provide security both for the hospitals and for pilgrims journeying back and forth to Jerusalem from the coast. Support for the order’s work — in the form of donations of lands and churches — began to come in from many parts of Europe. At Raymond’s death in 1160, the Order had posts in England, Germany, Poland, Denmark, and elsewhere. This process would continue; the prowess of the Knights of St. John in battle against the Saracens was such that, with their brother (and sometimes rival) orders of the Temple, the Teutonic Knights, and St. Lazarus, they became the shock troops of the Crusades. The Kings of Jerusalem entrusted to them such important castles as Krak des Chevaliers and Margat in Syria and Belvoir in Israel.

TIZIANO Vecellio, A Knight of Malta, 1510-15, Oil on canvas, 80 x 64 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The spirituality of the Order came from its rule, and encompassed a unique take on the perception of God, the Liturgy, the Sacraments, and much else besides. Perfectly suited to the combination of military and medical skill the Knights were called upon to exercise, their influence extend to many later and smaller orders founded in their wake.

This strong but tender religious outlook would be much need by the members of the Order, who would face misfortunes that would have crushed other organizations. On July 4, 1187, the Knights Hospitaller (as they were also often called) were caught up with their Templar brethren and many of the lay knights of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the disastrous defeat of Hattin. Not only were the better part of the Order’s knights killed, but in the aftermath, most of the cities of the kingdom, including Jerusalem, fell to Saladin. A few coastal cities hung on, and Richard the Lion Heart, Philip August of France and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa set off on the Third Crusade. A much reduced Kingdom (with its capital at Acre, where the Knights of St. John transferred their headquarters) soldiered on for another century; but in 1291 Acre fell. The Crusades were over, and the great military orders were left without either home or object.

They were not, however, without resources. Each of the Orders had a network of Commanderies throughout Europe. Initially relocating to Cyprus, they sought new missions. The Teutonic Knights eventually migrated to the Baltic, to subdue the pagan populations of what are now East Prussia, Latvia, and Estonia. The Order of St. John went to Rhodes, where they fought Muslim pirates. The Templars were unable to redefine themselves; their many possessions and possible moral failings led to their suppression. Those of their lands that were not taken by various kings went to the Hospitallers: in this way, the Templar headquarters in London (where they rented space to local barristers) and Paris (which served as the French Royal family’s prison during the revolution) came into the Order’s hands.

This property was necessary; it went to support the Knights’ never-ending war against the pirates — a work rendered all the more important by the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453. It is important to remember what capture by these corsairs actually meant — not only loss of cargo, but being held for ransom for the wealthy, and slavery or (for the more attractive women and boys) the harem for the poor. These “Barbary Pirates” ranged as far as Iceland and Ireland, carrying whole villages off into captivity. Moreover, these same pirates provided naval support for the ongoing Turkish invasion of Eastern Europe. Often outgunned and outmanned, it was against this threat that the Knights of the White Cross pitted themselves.

VERONESE, Paolo, Battle of Lepanto, c. 1572, Oil on canvas, 169 x 137 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

Not well pleased with this opposition to his minions, twice — in 1480 and 1522 — the Ottoman Sultan besieged Rhodes, the second time successfully. Once more, the Knights were homeless. But not for long. In 1530, the Holy Roman Emperor (and King of Spain) Charles V gave them Malta and the newly liberated city of Tripoli; the one to continue their struggle against the pirates, the other simply to hold onto. Once again, and with great effectiveness, the galleys of the Knights scoured the seas. Twenty one years later, their reckoning with the Turks would come; in July of 1551, the Turks were defeated in a siege of Malta, but made off with 5,000 Maltese captives. In August they attacked Tripoli, which fell after a six day siege. In 1565 another attack with overwhelming forces was made on Malta, but the outnumbered knights, under their brave and saintly Grand Master, Jean de la Vallette, drove them off. Six years later, ships of the Order were part of the fleet that crushed the Ottoman threat at Lepanto.

Unfortunately, this victory came while the Church and the Order were in the midst of another struggle, just as dire. The Protestant revolt tore Northern Europe from the Church, and both the Maltese and the Teutonic Orders suffered tremendous losses in lands and personnel. For the Order of St. John it meant the loss of the British Isles, Scandinavia, and most of north Germany: most, but not all. The Bailiwick of Brandenburg turned Protestant, but retained a tenuous connection with Malta. Henry VIII and the Scots Protestant lords seized the Order’s property in their respective realms — amongst the casualties being the London Temple, the complex near there at Clerkenwell, and the Scottish headquarters at Torphichen. The latter was seized by the head of the Order in Scotland, James Sandilands, who in his turn married and became Lord Torphichen. Ironically, his descendant, the father of the present Lord, converted to Catholicism and became himself a Knight of Malta.

MOR VAN DASHORST, Anthonis, Knight of the Spanish St. James Order, 1558, Oil on oak panel, 44 x 35 cm, Szépmûvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

While the Turkish strategic threat was ended to Europe with Lepanto, the struggle went on against the pirates for another 230 years. In that time, the Knights kept the sea-lanes safe. Moreover, to gain training in their craft, many of the knights spent time in foreign navies. One of their number, Admiral Suffren, one great fame with the French fighting the British Royal Navy in the Indian Ocean during the American Revolution. So things went until 1792.

In that year, the French revolutionaries seized all the properties of the Order in their country, from whence came a large part of the Knights’ income. Then, as their armies annexed neighboring areas, every territory of the Order they encountered was similarly taken away. At last, while en route to Egypt in 1798, Napoleon arrived at Malta itself. Without much resistance (some say treacherously, though it is a matter of dispute), the Grand Master, Ferdinand von Hompesch, surrendered. Once again the Order was homeless.

Attempting to regain Malta through diplomatic means, most of the knights (save those of Spain and Rome) agreed to the election of Tsar Paul I of Russia as Grand Master by mid-1799. The records of the Order, as well as its three great relics — a piece of the Truce Cross, a fragment of St. John the Baptist’s skull, and an icon of Our Lady of Philermos — were duly dispatched to St. Petersburg. Not only did Paul I create a Catholic Priory for Russia, he started an Orthodox one as well. Moreover, he gave the new priory the church of St. John the Baptist on St. Petersburg’s Stone Island, and the Vorontsov Palace (now the Suvorov Military Academy); next to the latter the Tsar Giovanni Quarenghi build a Maltese chapel. At the Imperial estate of Gatchina the Priory Palace was built and used for meetings of the Order’s leadership, and a palace and church given them at Tsareskoye Selo as well. Paul established a number of hereditary commanderies in the Order for various Russian noblemen, and had the order funded out of the Imperial treasury.

VELÁZQUEZ, Diego Rodriguez de Silva y, Portrait of a Knight of the Order of Santiago, c. 1635, Oil on canvas, 67 x 56 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

Despite this all this largesse, the fact remained that Paul was Orthodox and not Catholic, and that the Pope did not recognize his Mastership over the Order. He was in any case assassinated in 1801. His son and successor, Alexander I, although friendly to Catholicism, recognized that he had no right to rule the Knights. He renounced his control, sending the archives back to Italy. (He held on to the Great Relics however; after many adventure following the Russian Revolution they ended up in Montenegro where the government is building a shrine for them to attract Catholics and Orthodox alike). In any case, the Order would be run by Lieutenants instead of a Grand Master for the next seventy-eight years.

The Knights were still without a home, however. At the Treaty of Amiens, the British agreed to return Malta (which they had occupied) to them, but they reneged. In 1806, the King of Sweden offered them the large Baltic Isle of Gotland. But as the Pope advised against acceptance given that it would be a surrender of their right to Malta, the Knights declined. The administration moved to Sicily — first Catania, then Messina — but none of it was permanent, and the various scattered knights were essentially on their own.

One unintended consequence of the expulsion of the Knights from Malta was that the Barbary Pirates began to rage once more with a ferocity and reach unseen in centuries. The various European powers and the United States tried buying them off — and the difficulties resulted in the arrival of a handful of U.S. Marines at “the Shores of Tripoli.” But their threat was unstoppable until the French invaded Algeria in 1830. At that point, however, the schemes on the part of various Catholic Sovereigns to regain a place for the Knights in the Mediterranean ended.

In 1827 the government of the Order moved to Ferrara in the Papal States, and then in 1831 to the Palace of the Grand Prior of Rome on the Aventine Hill (now called the Villa Malta). A few years later, it moved to the residence of their Ambassador of the Holy See (now called the Palazzo Malta, and still seat of the Grand Magistery. From this point on may be dated the slow recovery of the Order to its present state. The French branch of the Order — without the permission of the Lieutenant — had begun creating English Protestant knights, who regarded themselves as the successors of the English section of the Order. This, although deprived of its property, had never been legally abolished. The Palazzo Malta forbade the practice, but the now fairly numerous Anglican knights formed what has since become the Venerable Order of St. John. Impressed by their charitable and medical work, Queen Victoria made them part of the British Honors system, and became their “Sovereign Head.” Spreading across the British Empire, it has since become a world-wide body.

Queen of Angels Foundation Founding Chairman, Mark Anchor Albert, Esq., KM, in the official Church robes of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes, and of Malta. The Maltese Cross on the robe represents, on the one hand, the eight lands of origin of the Order of Malta, or Langues. The eight points also symbolize, on the other hand, various attributes which Knights and Dames of Malta seek to cultivate in themselves as members of the Order in service of the Church and the Sick and Poor, our “Lords”: Loyalty; Piety; Generosity; Bravery; Glory and honor; Contempt of death; Helpfulness towards the poor and the sick; Respect for Mother Church. In this later sense, the eight points of the Maltese Cross of the Order of Malta also sometimes are said to represent the eight Beatitudes.

The interwar years saw the Orders organization strengthened and its activities extended. World War II saw innumerable challenges, as the Knights with rest of Europe were thrust between the hammer of Hitler and the anvil of Stalin. Yet the national associations did their duty to the sick and wounded, and a number lost their lives. The war produced another martyr-knight, Bishop Baron Vilmos Apor, who lost his life to Soviet troops attempting to break into his residence to rape the women hiding there on Good Friday, 1945. The bishop died, but the women were saved. As with the Emperor Charles, whose loyal subject he had been, he faced death with the same knightly spirit that animated those first Hospitallers in the Holy Land and the defenders of Rhodes and Malta.

Since the end of World War II, the activities of the Knights of Malta have mushroomed. The Dutch and Swedish branches seceded from the Protestant German Johanniter, successors to the Knights who accepted Lutheranism. But all three groups have continued to expand their activities. In 1961, together with the Venerable Order of St. John, the three Continental Orders formed the Alliance of the Orders of St. John of Jerusalem which established a permanent headquarters in Geneva. The Sovereign Order of Malta signed an agreement of recognition with the group in 1987, which opened with the words “With the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta which is Roman Catholic, the four non-Catholic Orders of St. John provide a Christian answer to the problems of a troubled and materialistic world. They have a common devotion to a historical tradition and a unique vocation: the lordship of the sick and the poor. They strive to realize their aim by mutual collaboration as well as by their own works. They are the only Orders of St. John which may legitimately use that name.”

This last sentence points up one of the major reasons for the agreement. As well as cooperation in the charitable sphere, the five orders have formed a “False Orders Committee,” which strives through legal means to prevent the use of the name “Order of St. John” or “Order of Malta” by self-originating groups which have mushroomed since World War II. Usually claiming some sort of descent from the Russian branch of the Order and basing their claims on spurious history, they have added a great deal of confusion (and sometimes scandal) to the names they appropriate. Interestingly enough, there is an organization of descendant’s of Tsar Paul’s hereditary commanders, but it makes no claim to be an order. One of these organizations did have the protection of the exiled King Peter II of Yugoslavia, but his son, Crown Prince Alexander, has not kept up this interest.

In 1988, Fra Andrew Bertie (a cousin of Queen Elizabeth II), the first Englishman to hold the post, was elected Grand Master. Two decades later, after his death, he was succeeded by a countryman, Fra Matthew Festing. Recently, the Order leased Fort St. Angelo on Malta from the government for a period of 99 years — so, in a way, the knights have come home.

It is a long way in time and space from that first hospital in Jerusalem to the Free Clinic here in Los Angeles. Yet, despite the many bumps and catastrophes along the way, the Sovereign Military Order of Malta has managed to stay true to its original goals — the protection and care of the sick and suffering. The Archdiocese if Los Angeles is fortunate to have them here.